I know that DNA encodes proteins. Truthfully, everything besides that (including ‘what are proteins’) mostly wooshes over my head, but that’s not relevant because whenever I search this question I never even find it addressed anywhere.

The human body has, among other things, two hands each with five fingers, with a very particular bone structure. How are things like that encoded in DNA, and by what mechanisms does that DNA cause these features to be built the way they are? What makes two people have a different nose shape? Nearly everyone in my family has a mole on the left side of their face, how does that come about from DNA?

I’m sure there are many steps involved, but I don’t see how we go from creating proteins to reproducibly building a full organism with all the organs in the right places and the right shapes. Whenever I try to look this up, all of these intermediate steps are missing, so it basically seems like magic.

As I said, any explanation will most likely go over my head and I won’t be able to understand it fully, but I at least want to see an explanation. I’ll do my best to understand it of course.

I recently had a course in developmental biology and this is what I can remember the best:

From the moment of fertilization, the egg has a ‘polarity’, thus a direction like up and down, left and right etc. This can be established by e.g. the entry point of the sperm or protein produced by the mother in one side of the egg. From here on out protein gradients and interactions on cell membranes specify where cells are and thus what kind of tissue they should become

This early polarity leads to a certain pattern of cell division. An important part of this is the folding in of tissue layers called gastrulation, creating the beginning for the gastrointestinal tract.

In vertebrates a streak starts to form in the embryo. This is the start of the vertebrae and the neural tube in it. Also blocks of cells called somites start to form. These blocks are very important for all kinds of tissues in the body.

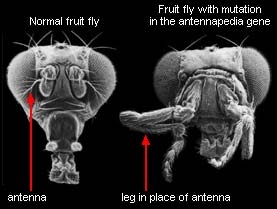

Hox genes make the cells in somites get an identity like head, arm etc. So in the end Hox genes are probably what you are looking for. If leg Hox genes are expressed where fruitfly normally have antennae, you get this horror:

So in the end Hox genes are probably what you are looking for.

Thank you! I will read up on that.

If leg Hox genes are expressed where fruitfly normally have antennae, you get this horror:

So, a core part of my question is what causes certain genes to be expressed in certain places in the body, and specifically how this comes about from genetics alone (i.e. not artificially in lab experiments). In my past searches I did find some info about forcing gene expression in places where it wouldn’t normally happen, which creates horrors similar to the one you shared, but I never found an answer for how this is controlled in natural development. Hox genes seem to be the answer I’m looking for :)

Here’s a fantastic and entertaining short video on how it works: https://youtu.be/ydqReeTV_vk?si=AyKJPZIzwaSCvZxv

Huh… it never ceases to amaze me how many quite large channels that I would absolutely enjoy, like this, are not recommended to me. Even though I watch content very similar and live on YT.

Thanks for sharing.

How is this so good hole crap

By the way, in case you’d have a guess for the answer:

If scientists really wanted to, throwing all questions of ethics out the window, would it be possible to genetically engineer a person with four arms instead of two, kinda like Goro? Does our current understanding of this go far enough to make deliberate changes like that? And would that baby be able to develop in a normal woman’s pregnancy?

No, and no. My PhD thesis was on gene delivery. We’re barely getting into the simplest modifications for disease treatment. Multigene stuff, and spatiotemporal control is still a ways off.

I would say sort of. They could do it, but the result wouldn’t survive very long. Probably not even to birth.

This is pretty much the underpinning question of the entire field of evolutionary developmental biology, so naturally any answer is going to be a bit surface level, and I get out of my depth fairly rapidly to be honest. Still, it is quite interesting.

One of the central ideas is that as an embryo grows, its cells go from being all equivalent multipotent stem cells into being different from each other - at first more specialized types of stem cell that can only turn into certain tissues and gradually specializing more and more. Since these cells are differentiated and expressing different genes from one another, they can then start to co-ordinate with each other using chemical markers and gradients of concentration of those markers across space to regulate what types of cells should be growing/dividing, where in the embryo they should be doing it and at what time they should be doing it.

That signaling is in turn controlled by some often complicated networks of regulatory genes - ones which when they are expressed make proteins that selectively attach to other bits of the DNA in that cell and make the genes there more or less likely to be expressed themselves. A lot of evolutionary variation is actually focused on these regulatory systems rather than on the genes which they are switching on and off.

So to my knowledge, something like nose shape likely comes down to some of those regulatory genes controlling where the cells that will eventually be forming the cartilage get placed relative to the skull etc.

A good introductory explanation: https://coldbloodedscience.com/the-art-of-shape/

https://youtu.be/ydqReeTV_vk?si=ZvLCP_YhY-OsB_Zs General overview in an entertaining wrapping

This was posted a few hours before your comment by a user named neuropean. It’s absolutely amazing!

I’ll focus on a side question, that I’m more prepared to answer.

Truthfully, everything besides that (including ‘what are proteins’) mostly wooshes over my head

At the end of the day, proteins are biiiiig arse molecules. Mostly composed of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. For example, here’s a protein called “myoglobin”, that carries oxygen within your blood:

Blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, grey = carbon, white = hydrogen, salmon = iron, yellow = sulphur. Disregard the mix of sticks and balls in the model, they’re both representing atoms.

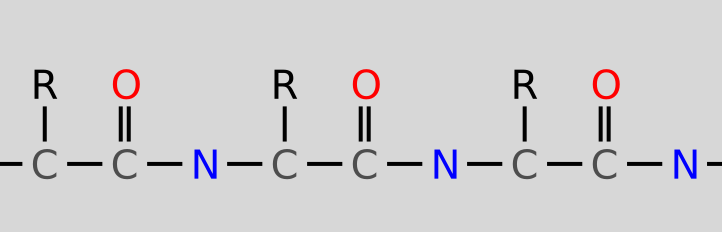

If you pay close attention to the model, you’ll notice a repetitive pattern: 1) nitrogen, 2) carbon connected to some large junk, 3) carbon connected to a “dangling” oxygen. That is not just in the myoglobin, but in all proteins.

If you flattened that pattern and removed the hydrogens (to simplify it), you’d get something like this:

That happens because the bodies of living beings don’t build those huge molecules out of nowhere; they do it with smaller molecules called “aminoacids”. That pattern there is the amide group, you could see it as the “solder” between aminoacids.

Here’s the representation of a few “free” aminoacids:

The fun part is that R, the “side chain”. I called it “junk” but it’s actually a big deal - because it’s what gives each protein a different shape and property. For example, it’s thanks to that junk that the myoglobin has a specific shape, that forms a “ring” of nitrogens, just at the right size to host an iron cation, but still leaves one of the sides of the iron cation free - so it could connect to something else. (Hopefully diatomic oxygen. As in, it’s how myoglobin transports that oxygen within your body. But if you get poisoned with carbon monoxide or cyanide, it gets stuck there, and it’s hard to take it off so the protein stops transporting oxygen.)

For example, here’s a protein called “myoglobin”, that carries oxygen within your blood:

Myoglobin is in the muscles. Hemogoblin is in the blood and is essentially 4 myoglobin molecules that can combine into one hemoglobin. IIRC, the combination of the 4 makes it easier to switch between accepting and donating oxygen, where myoglobin is better just at the taking oxygen.

The R side chains are not referred to as radicals. R- is common in organic chemistry and refers to a part of a molecule not shown for some reason. Generally because it’s not the focus in the specific figure. Generally you’ll have a R = (whatever combination of atoms) defined below.

Radicals are a specific atom with an unpaired valence electron. Sometimes also called “free radicals”.

Edit, here’s an example of a non-amino acid use of R: